Maybe I should start with the good things: the man who, upon noticing us pulled over on the side of the road, offered to lead us to where we were trying to go; the hostess who joked around with me as I went to meet my husband who had been seated at a restaurant earlier than expected; the friendly waiter who brought us rakija and joined customers in taking shots; our host, who texted me recommendations for where I should go run. I firmly remember the good things. I would go back. I had a great time. People seemed genuinely hospitable, more so than many other places I’ve been. But it is not the good things that my thoughts prod at, that curdle in my mind.

It’s the fact of neighbors turning into genocidal murderers.

We wandered around Mostar during our first afternoon in the city. It didn’t take long to notice bullet holes that pecked the sides of buildings. We walked past a building that had been shelled and now stood grey and abandoned just a few blocks from the central market. On the other side of the Neretva River, a brutalist edifice looms near the secondary school, which stood at the front line of the Bosnian War: Sniper Tower, formerly a bank. We circled the building. How many people were murdered from right above us?

We walked past a graveyard as we made our way back toward where we were staying. Every single grave that I saw listed 1992 as the year of death—the first year of the Siege of Mostar. I checked the birth years; many were young.

The following day, we walked by a different cemetery. Every death date that I saw was in 1993.

I went out on a run, gradually headed toward a park that our AirBnb host told me was a good spot. When mapping out my route, I realized that I would be near the Partisan Memorial Cemetery, so I decided to run there on my way to the park. I passed the spot where I thought the memorial entrance should be, but I didn’t see signs or even a developed path. I continued to the park, thinking there was perhaps a back entrance; I promptly found myself on a too-overgrown trail, so I turned around. As I ran back the way I came, I pulled out my phone to try to see here I had gone wrong. My GPS told me it was right there. Eschewing dedicated paths this time, I crossed some street construction, jogged up a barely noticeable gravel path, and there it was.

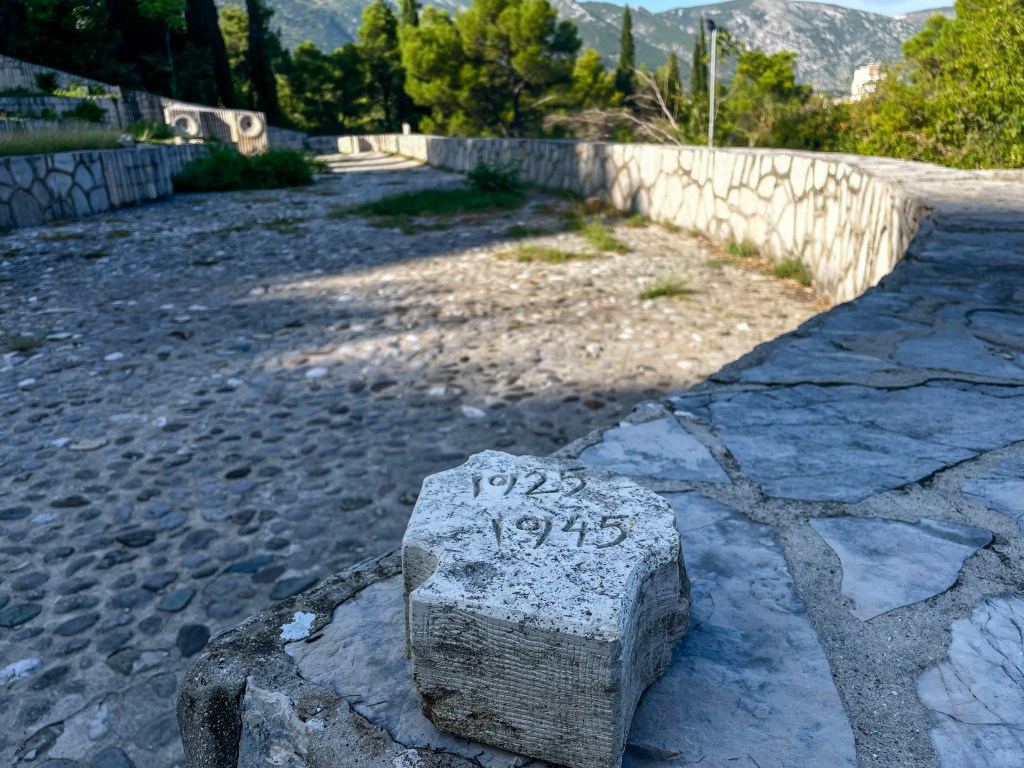

The Partisan Memorial Cemetery was completed in 1965 to honor the Yugoslav Partisans who were killed in World War II as they fought against the Nazi puppet government of Croatia, the fascist Ustaša regime. The memorial was badly damaged in the Bosnian War but had been fixed up and re-opened years later. I paused my run and began walking to the heart of the memorial. No one else was around. The sun shone down on the overgrown path, graffiti on the walls, stones strewn everywhere. I took some photos, in awe despite the disrepair, then ran back to where we were staying.

Run complete, I decided to read more about the memorial. The stones I had been stepping over were smashed memorial markers; a year prior, every one of the nearly 700 had been systematically destroyed in an attack.

Later that day, I returned with my husband to show him the site. Again, the memorial was deserted, though we passed a German couple on their way out. The woman turned to me in shock: “Everything is destroyed; it’s unthinkable.”

This time, I noticed patterns in the rubble. Someone had organized chunks of memorial markers into a neat pattern toward the top of the memorial. As we wandered through, I paid more attention to the graffiti. The Ustaša symbol was all over. Underneath attempted cover-ups I could make out swastikas.

If you find yourself in Mostar, you must go to the Museum of War and Genocide Victims 1992-1995. The museum is run by survivors and shares individuals’ experiences through donated items: someone’s jacket, a child’s doll, letters, a mug. All are accompanied by stories. The most horrifying to me were those that told of their neighbors turning on them, burning and looting their homes and chasing them away with threats of rape and death. One person sounded shocked in their narrative: we had no problems with them, we got on well, and then…

Among the mementos is a screen that shows a video of the shelling and collapse of Mostar’s Old Bridge in 1993. This bridge had stood since 1566. Croatian troops shout and cheer as it crumbles.

The final room is covered in colorful notes that visitors have written. Over and over, people exclaim about our shame, then and ongoing. Never Again, unfortunately, never happened.

On our last morning in Mostar, we walked to a nearby coffee shop before hitting the road. As we ordered, outing ourselves very obviously as foreigners, an older middle-aged man began speaking to us in English, asking where we were from, where we were staying, and so on. These questions could have been innocuous, but the man was too friendly, aggressively friendly. He started telling us about how he had connections to the United States through his church; I politely listened for a minute but then ducked outside for fresh air and to avoid being talked at further.

When I went in to pay the bill, the man began chatting at me again. I noticed a scorpion tattoo on his neck. Instinctual alarm bells rang in my head as I told him I was leaving, goodbye. He held out his hand and I shook it before getting out of there.

I knew the scorpion meant something and immediately looked it up. There it was: the Scorpions were a paramilitary group active during the Yugoslav Wars that, among other things, helped perpetrate the Srebrenica massacre. The tattoo on the man’s neck matched their insignia. And there he sat, tattoo uncovered, conversing with others in the smoky café, unbothered.

We left Bosnia and Herzegovina (the federation, not the country) and drove into Republika Srpska, an autonomous political entity within Bosnia and Herzegovina (the country; yes, I know it’s a bit confusing). Street signs shifted to Cyrillic from predominantly Latin script (or Latin above Cyrillic, with the latter sometimes covered up). Periodically, we would pass by roadside stands. We stopped at one, and I bought some walnut rakija with the help of google translate. The vendor was very proud of his honey as well, but I doubted we could get that through customs. Purchase made, the friendly man waved us off. I can tell you now: his rakija is delicious.

A short while later, we stopped in Trebinje to explore and eat a late lunch. Prior to the Bosnian War, though majority Serb, the town was ethnically mixed and Muslims made up about 18% of the population. Few remain today, after practically the entire Muslim population was violently expelled in 1993, their homes taken over by Serbs, and many of their mosques burned down.

At the top of a hill overlooking the town stands a newer Orthodox church. People flocked around taking photos. The vast majority did not seem to be foreign tourists like us. After this, we descended to wander through the old town. A hundreds-year-old mosque remains there, but no one was taking photos by it.

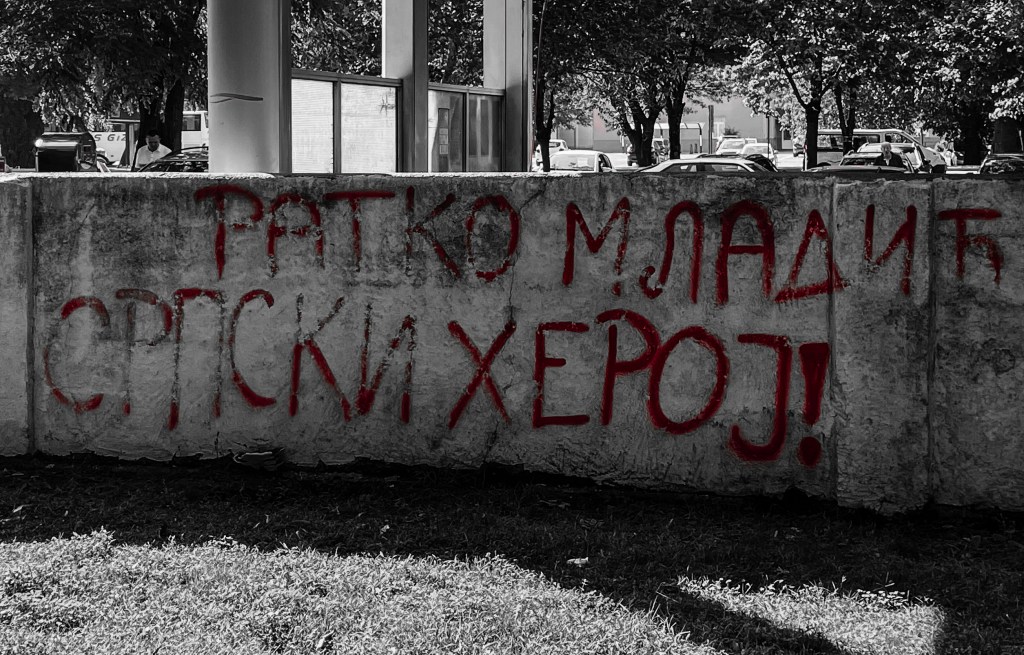

On our way back to our car, we walked through the park just next to the old town. I read some graffiti and audibly gasped. “Kosovo is Serbia!” “Not one meter less! 10908km2” “Ratko Mladić, Serbian hero!”

10908km2 is the size of Kosovo. Ratko Mladić is a war criminal, convicted at the Hague for genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes.

The graffiti was untouched.

Share Your Thoughts